Berkshire Hathaway 2006 Annual Report Download - page 9

Download and view the complete annual report

Please find page 9 of the 2006 Berkshire Hathaway annual report below. You can navigate through the pages in the report by either clicking on the pages listed below, or by using the keyword search tool below to find specific information within the annual report.

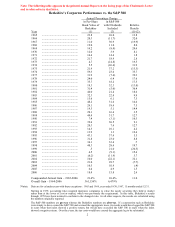

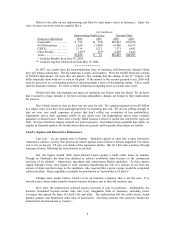

Below is the tally on our underwriting and float for each major sector of insurance. Enjoy the

view, because you won’ t soon see another like it.

(in $ millions)

Underwriting Profit (Loss) Yearend Float

Insurance Operations 2006 2005 2006 2005

General Re ....................... $ 526 $( 334) $22,827 $22,920

B-H Reinsurance.............. 1,658 (1,069) 16,860 16,233

GEICO ............................. 1,314 1,221 7,171 6,692

Other Primary................... 340** 235* 4,029 3,442

Total................................. $3,838 $ 53 $50,887 $49,287

* Includes MedPro from June 30, 2005.

** Includes Applied Underwriters from May 19, 2006.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

In 2007, our results from the bread-and-butter lines of insurance will deteriorate, though I think

they will remain satisfactory. The big unknown is super-cat insurance. Were the terrible hurricane seasons

of 2004-05 aberrations? Or were they our planet’ s first warning that the climate of the 21st Century will

differ materially from what we’ ve seen in the past? If the answer to the second question is yes, 2006 will

soon be perceived as a misleading period of calm preceding a series of devastating storms. These could

rock the insurance industry. It’ s naïve to think of Katrina as anything close to a worst-case event.

Neither Ajit Jain, who manages our super-cat operation, nor I know what lies ahead. We do know

that it would be a huge mistake to bet that evolving atmospheric changes are benign in their implications

for insurers.

Don’ t think, however, that we have lost our taste for risk. We remain prepared to lose $6 billion

in a single event, if we have been paid appropriately for assuming that risk. We are not willing, though, to

take on even very small exposures at prices that don’ t reflect our evaluation of loss probabilities.

Appropriate prices don’ t guarantee profits in any given year, but inappropriate prices most certainly

guarantee eventual losses. Rates have recently fallen because a flood of capital has entered the super-cat

field. We have therefore sharply reduced our wind exposures. Our behavior here parallels that which we

employ in financial markets: Be fearful when others are greedy, and be greedy when others are fearful.

Lloyd’s, Equitas and Retroactive Reinsurance

Last year – we are getting now to Equitas – Berkshire agreed to enter into a huge retroactive

reinsurance contract, a policy that protects an insurer against losses that have already happened, but whose

cost is not yet known. I’ ll give you details of the agreement shortly. But let’ s first take a journey through

insurance history, following the route that led to our deal.

Our tale begins around 1688, when Edward Lloyd opened a small coffee house in London.

Though no Starbucks, his shop was destined to achieve worldwide fame because of the commercial

activities of its clientele – shipowners, merchants and venturesome British capitalists. As these parties

sipped Edward’ s brew, they began to write contracts transferring the risk of a disaster at sea from the

owners of ships and their cargo to the capitalists, who wagered that a given voyage would be completed

without incident. These capitalists eventually became known as “underwriters at Lloyd’ s.”

Though many people believe Lloyd’ s to be an insurance company, that is not the case. It is

instead a place where many member-insurers transact business, just as they did centuries ago.

Over time, the underwriters solicited passive investors to join in syndicates. Additionally, the

business broadened beyond marine risks into every imaginable form of insurance, including exotic

coverages that spread the fame of Lloyd’ s far and wide. The underwriters left the coffee house, found

grander quarters and formalized some rules of association. And those persons who passively backed the

underwriters became known as “names.”

8