Berkshire Hathaway 2009 Annual Report Download - page 14

Download and view the complete annual report

Please find page 14 of the 2009 Berkshire Hathaway annual report below. You can navigate through the pages in the report by either clicking on the pages listed below, or by using the keyword search tool below to find specific information within the annual report.Dave Sokol, the enormously talented builder and operator of MidAmerican Energy, became CEO of

NetJets in August. His leadership has been transforming: Debt has already been reduced to $1.4 billion, and, after

suffering a staggering loss of $711 million in 2009, the company is now solidly profitable.

Most important, none of the changes wrought by Dave have in any way undercut the top-of-the-line

standards for safety and service that Rich Santulli, NetJets’ previous CEO and the father of the fractional-

ownership industry, insisted upon. Dave and I have the strongest possible personal interest in maintaining these

standards because we and our families use NetJets for almost all of our flying, as do many of our directors and

managers. None of us are assigned special planes nor crews. We receive exactly the same treatment as any other

owner, meaning we pay the same prices as everyone else does when we are using our personal contracts. In short,

we eat our own cooking. In the aviation business, no other testimonial means more.

Finance and Financial Products

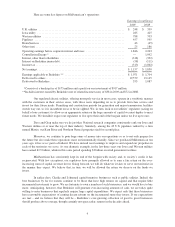

Our largest operation in this sector is Clayton Homes, the country’s leading producer of modular and

manufactured homes. Clayton was not always number one: A decade ago the three leading manufacturers were

Fleetwood, Champion and Oakwood, which together accounted for 44% of the output of the industry. All have

since gone bankrupt. Total industry output, meanwhile, has fallen from 382,000 units in 1999 to 60,000 units in

2009.

The industry is in shambles for two reasons, the first of which must be lived with if the U.S. economy

is to recover. This reason concerns U.S. housing starts (including apartment units). In 2009, starts were 554,000,

by far the lowest number in the 50 years for which we have data. Paradoxically, this is good news.

People thought it was good news a few years back when housing starts – the supply side of the picture

– were running about two million annually. But household formations – the demand side – only amounted to

about 1.2 million. After a few years of such imbalances, the country unsurprisingly ended up with far too many

houses.

There were three ways to cure this overhang: (1) blow up a lot of houses, a tactic similar to the

destruction of autos that occurred with the “cash-for-clunkers” program; (2) speed up household formations by,

say, encouraging teenagers to cohabitate, a program not likely to suffer from a lack of volunteers or; (3) reduce

new housing starts to a number far below the rate of household formations.

Our country has wisely selected the third option, which means that within a year or so residential

housing problems should largely be behind us, the exceptions being only high-value houses and those in certain

localities where overbuilding was particularly egregious. Prices will remain far below “bubble” levels, of course,

but for every seller (or lender) hurt by this there will be a buyer who benefits. Indeed, many families that couldn’t

afford to buy an appropriate home a few years ago now find it well within their means because the bubble burst.

The second reason that manufactured housing is troubled is specific to the industry: the punitive

differential in mortgage rates between factory-built homes and site-built homes. Before you read further, let me

underscore the obvious: Berkshire has a dog in this fight, and you should therefore assess the commentary that

follows with special care. That warning made, however, let me explain why the rate differential causes problems

for both large numbers of lower-income Americans and Clayton.

The residential mortgage market is shaped by government rules that are expressed by FHA, Freddie

Mac and Fannie Mae. Their lending standards are all-powerful because the mortgages they insure can typically

be securitized and turned into what, in effect, is an obligation of the U.S. government. Currently buyers of

conventional site-built homes who qualify for these guarantees can obtain a 30-year loan at about 5

1

⁄

4

%. In

addition, these are mortgages that have recently been purchased in massive amounts by the Federal Reserve, an

action that also helped to keep rates at bargain-basement levels.

In contrast, very few factory-built homes qualify for agency-insured mortgages. Therefore, a

meritorious buyer of a factory-built home must pay about 9% on his loan. For the all-cash buyer, Clayton’s

homes offer terrific value. If the buyer needs mortgage financing, however – and, of course, most buyers do – the

difference in financing costs too often negates the attractive price of a factory-built home.

12